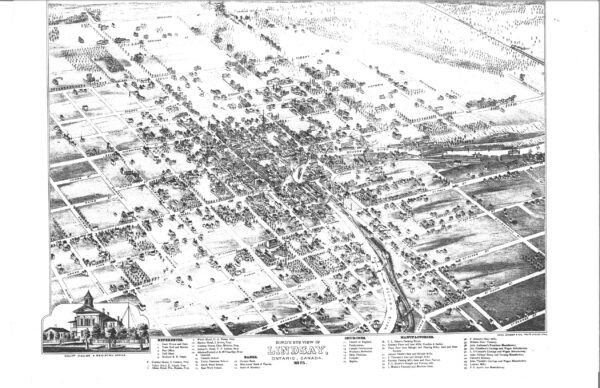

Putting Lindsay on the map: Herman Brosius’ “Bird’s Eye View” of 1875

It is mid-autumn of 1875, and a golden eagle is soaring over the little town of Lindsay as it wanders about during the annual migratory season. Flying through the late afternoon sky, it may well have encountered flocks of geese and warblers as they made their way south (in numbers many billions more then, than now). With a graceful loop, the eagle turns around and for a few moments points its beak in a northwesterly direction, descending in altitude to get a closer look at the bustling community unfolding below. And what would it have seen? A winding river flanked by busy factories, trains going hither and yon, stately spires, and a grid of tree-lined streets home to a growing population that would work in those factories, ride those trains, and worship in those churches.

All of this was captured on the “Bird’s Eye View of Lindsay, Ontario, Canada,” a map first released 150 years ago and has been sparking curiosity ever since. A large copy hangs in the reference department at the Kawartha Lakes Public Library’s Lindsay branch; it occupies the frontispiece of Bless These Walls (a book about Lindsay’s architectural heritage published in 1982); and reproduction prints are available at the Kawartha Lakes Museum & Archives.

But who was responsible for it, and how did they draw it in an age before aerial photography took off? And what features of the map remain on the ground today, a century and a half after the unnamed artist finished his drawing?

As North America’s towns and cities grew during the late 19th century, Bird’s Eye View maps – properly called panoramic maps – became popular media, and were often used for promotional purposes. Artists would visit a community, drawing pencils in hand, and walk up and down the principal streets making sketches of buildings and other details. Artistic licence might have been taken here and there (e.g. pencilling a boat into the river). These drawings were then copied into a map of the community that was made using isometric projection. The result was a detailed depiction of a town or city, captured in three dimensions on a two-dimensional sheet of paper.

There were many talented artists who made this type of work their specialty. Based on striking similarities to other panoramic maps done during the same period, it is all but certain that the individual behind Lindsay’s panorama was an American cartographer named Herman Brosius. Born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in 1851, Brosius was well-travelled. While in his early 20s, Brosius spent about six years exploring half a dozen small towns in Ontario – including, it seems, Peterborough and Lindsay. Though he was responsible for nearly 60 Bird’s Eye Views, Brosius was rarely credited on the drawings themselves; the only name on Lindsay’s map is Charles Shober & Co., the Chicago-based firm responsible for printing the map.

Based on contemporary reportage, it seems likely that Brosius appeared in Lindsay towards the end of 1874. “Some time ago we noticed that an artist was taking sketches of Lindsay for the purpose of giving a bird’s eye view of the town,” reported the Canadian Post on Jan. 8, 1875. “Similar maps have been made of Peterboro, Port Hope, Belleville, Kingston, Brockville and other Canadian towns, and have given universal satisfaction,” the Post continued. “The people have liberally supported it, and the Councils in those places have ordered from fifty copies upwards.” (Although the panorama was paid for by subscription, W.A. Goodwin, proprietor of the local art store, placed advertisements in the Post that spring for “The Bird’s Eye View of Lindsay, mounted and framed at the lowest living prices.”)

Much has changed in Lindsay over the past 150 years, of course. Some local landmarks we take for granted today, such as the Academy Theatre, the public library, and the present Presbyterian church, hadn’t been built when Brosius made his trek through town. Others, such as the various riverside mills and factories, have vanished from the landscape entirely, or – like the Needler & Sadler flour mill – have been reduced to ruins. Bond Street between Albert and Adelaide Streets is called Waverly Avenue in the Bird’s Eye View, and much of the east ward has yet to be developed. Meanwhile, a train steams northwestward in the upper right-hand corner of Brosius’ drawing – reminding us of how the railway redeveloped its right-of-way as Lindsay grew. (Those tracks were abandoned in 1907 in favour of a newer route running parallel to Durham Street, and vague traces of the embankment in the map still linger in the backyards of some properties on Orchard Park Road.)

Yet in other cases, time has stood still. The county courthouse (now city hall) and the old jail remain more or less as they were when Brosius drew them for his map, as does Lindsay’s town hall-turned-economic development office. The Albion Hotel at the northwest corner of Kent and Lindsay Streets is now home to various businesses, while the churches of Cambridge Street North continue to welcome worshippers Sunday by Sunday – as they did in 1875.

Herman Brosius died in 1917, but his map remains one of his most enduring artistic legacies.