Carley Reynolds on living with trauma, getting lost in colours, and the healing power of art

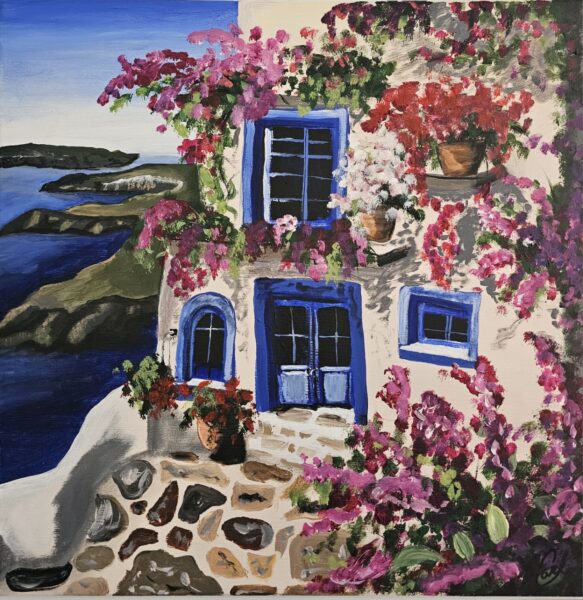

Greek Getaway is a lovely painting, with brilliant colours and uneven lines, evocative of old-world charm and splashes of possibility. I bought it for my home office two months ago from local Bobcaygeon resident and artist Carley Reynolds.

Maybe it reminds me of Leonard Cohen’s years on the Greek island of Hydra. On damp mornings here in Lindsay, when the sun is misplaced behind grey, I have imagined jumping into the painting and having a drink with Cohen – or at least some tea and oranges.

The notion of art as a portal to another world makes me wonder if that’s what Reynolds loves most about her craft. If so, who could blame her? The 33-year-old has had a life marked by trauma. Growing up in Haliburton with two brothers – all three siblings with different fathers – she was raised by a mother who was “an addict and an alcoholic,” according to Reynolds. Her father was not in the picture.

The home was one level with three bedrooms, sitting somewhere on top of the iconic Haliburton lookout. “Just one of those little houses in the bush,” she says.

Graz Restaurant in Bobcaygeon is humming on a late summer Monday as Reynolds retrieves more childhood memories.

Behind the house, there was “nothing but forest” and she would play in the woods with her dog, Fozzy, for hours on end. Closer to home, there was a shed where Fozzy would make like a groundhog, tunnelling under the structure. When she became overwhelmed and stressed out, Reynolds would join Fozzy where it felt like “nobody could get me.”

Reynolds was seven the first time she was sexually assaulted. One day she and her mother were watching Oprah, an episode that happened to be about abuse. While listening to the discussion on TV, the child recognized this had been happening to her – by her mother’s boyfriend – and told her so. Her mother turned off the TV, talked some more with her daughter, and then immediately called the police. It went through the court system, with Reynolds even taking the stand. She says the perpetrator got three months in jail.

Mental health concerns were a constant in the family. Reynold’s cousin was diagnosed as bipolar and ended up committing suicide. And then two months later, her aunt – her mom’s sister – committed suicide because she couldn’t cope with it. Reynolds had barely reached Grade 8 by the time this happened.

It’s time to order lunch and Jordan, our server, takes our twin food order of fish and chips, with a ginger ale for Reynolds and iced tea for me.

We zero in on her brothers, as they didn’t escape the childhood chaos, either. Her eldest sibling, Shawn – eight years her senior – was removed from their mother’s care and placed in a group home.

At around the same age – as if the universe sought some kind of balance – Reynolds got a “big sister” from the Big Brother Big Sisters non-profit. Her name was Janice, a hairdresser from Inglesby.

“She saved me. She showed me that there was more to the world than what I had so far experienced,” says Reynolds.

As she grew older, Reynolds found it increasingly difficult to get along with her mother, especially given her mom’s addictions. Shawn had been removed from the home when he was 14, already struggling with addiction and police run-ins. Similarly, London was also removed and placed in a group home due to drug use and getting into trouble with the law. Reynolds did not follow her brothers down that path but voluntarily left to escape her family. She found a foster family in Norland that saw her through her high school years with a welcome, positive influence.

“They were amazing. My (foster) dad’s a retired pastor and my (foster) mom’s a retired music teacher.”

Meanwhile, Reynolds’ big sister, Janice, who she affectionately called Sissy, continued to be a light that defied the darkness within Reynolds’ life. A stained-glass artist, a painter, and a hairstylist – the big sister perhaps seeded the future creative endeavours within the impressionable child.

They were supposed to see each other once a week, but Sissy made sure it was at least twice. They would also attend church together. “Sometimes I’d even sleep over at her house a little – we did more than most ‘littles’ and ‘bigs’ were allowed to do, but she bent the rules.”

Over the years, it gnawed at Reynolds that she knew nothing of her father.

Her mother was afraid of her dad, “so she wouldn’t even let me know his name. Every birthday, every Christmas, I just wanted my dad, and she hated that.”

Convincing her mom of this was futile, but Reynolds would soon have other concerns.

Sissy, who had become “my light in a very dark spot” was diagnosed with liver cancer. Knowing she didn’t have much time, the big sister made the little sister one promise – to find out the identity of Reynolds’ father. In the end, she did so by appealing directly to her mother as a dying wish for this information – and it worked.

Reynolds, in Grade 10 at this point, was then able to locate her father’s sister – and learned her dad had been looking for her for years, too. However, he had just died seven months earlier of cirrhosis of the liver. There would be no closure on this issue for Reynolds.

Months later, Sissy would die from cancer, too.

But the wrenching news didn’t stop there for Reynolds during this time in her life. About two weeks before Reynolds started Grade 12, her brother, London, overdosed on drugs. He died in hospital in front of her. Her mother was in no emotional shape to do anything at that time and so the teenager found herself being the main point of contact for the funeral home, taking care of arrangements.

“Those high school years were really rough. I lost a lot of people.”

Despite all her childhood setbacks – and with the support of the Children’s Aid Society system – Reynolds graduated from high school and enrolled in Travel and Tourism at Georgian College in Barrie.

A couple years later she added a short private investigating course to her CV and did work in this field for about a year.

“I just found it hard to sit in a car that long,” she says with a laugh, referring to the unglamorous aspects of the job. “I wanted to do the undercover work, but I got stuck doing surveillance.”

Later, in her mid-20s, she started dating someone in the automotive industry and ended up getting involved in car work herself. However, her relationship soured and she felt compelled to flee to a friend’s place in Halifax, her first time on Canada’s east coast.

She found a job at Honda and celebrated her 28th birthday out there – and then COVID hit. “So I was sitting with no money in a basement by myself. I was just in a scared state” with the pandemic adding to her anxiety.

When she got herself back to Ontario about a year later, she found yet another automotive job. While things were good for awhile, she realized a co-worker had been taking her clients in what was commission-based work. No support was forthcoming from her boss which added even more stress.

“I went into work on a Thursday, not thinking anything of it consciously, and then had a complete mental breakdown. I never returned again.”

She was 30 years old.

Reynolds says it was more than not feeling supported at work. It felt like she could no longer stave off all the trauma of her earlier years. It was like an unrelenting wave that she had held at bay for so long – one that would finally arrive to beach her entire life and force her to reckon with everything, all at once. The darkness of her childhood; the lack of a father; each fallen loved one; several sexual assaults from childhood through to her 20s; and not feeling supported at her job.

wagon for painting en plein air. Photo: Roderick Benns.

“Everything just collapsed on me.”

She became homeless for five months, living in a tent with her two dogs on her foster sister’s property.

Reynolds was diagnosed with Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (CPTSD), anxiety, depression, and panic attacks. (CPTSD is a mental health condition that can develop after prolonged or repeated exposure to traumatic events.)

She got help, thanks in large part to the Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA). They had an opening in Harrison House in Lindsay, a transitional, eight-bed, co-ed rehabilitative housing program for people with a diagnosed mental illness. The program helps people build life skills for independence and focuses on supporting mental health recovery in a goal-oriented way.

“I stayed for a year and a half, where you live with up to eight other people who are going through mental health or addiction issues.”

There were many programs to take part in at Harrison House. One night, it happened to be a paint night tutorial.

“That’s how I discovered I had an ability to paint.”

She continued to study YouTube tutorials on painting and found everything came naturally to her. Now, she has her own following on a streaming platform called Twitch and on Instagram. She’s learning to use TikTok.

“I’ve just been learning and painting, and it’s been an incredible journey.”

She thinks back to her more challenging younger adult years and the societal pressure then to know what she was supposed to do with the rest of her life.

“I was in a mindset where I just want to survive, right? You want me to figure out what I want to do for the rest of my life? No man, I just want to wake up tomorrow morning and be okay.”

In 2024 she was able to move to Bobcaygeon, a village she has come to love. And she still has an “amazing connection” with her foster family, which helps ground her.

Reynolds feels a certain level of validation to be where she is right now in her life.

“I grew up in a crappy environment. Everybody that I grew up with has (unplanned) kids, is dead, or on the system. I mean, I know I’m struggling right now too, but I’m trying every day. Every day is great, yeah?”

Reynolds has three small dogs – maltese – who act as her emotional support animals and who keep her going with a regular routine. Bellatrix, Mojo, and Felix are a family unit – a mom, dad and baby – and each morning she appreciates the routine they create.

“There are dogs to walk, there’s coffee to make, and then I’ve got to get streaming on Twitch,” she says, where she reaches about 60-plus followers (so far) who want to watch her paint, talk about her life, and share music and books. Mostly, they’re there for the journey. Reynolds uses the name Peace by Piece to describe her art business.

“I get to show the world how art can change your life.”

There is darkness she foresees on the horizon. She believes one day she will have to deal with her mother overdosing, just as she had to go through this with her brother, London.

“My mom’s done the best she could with what she’s had, which wasn’t much. As much as we’re talking about the trauma that I went through, she’s gone through it too, and she’s not had the support that I have had to be able to cope.”

Reynolds describes her mom’s parents as alcoholic and abusive, the sort of generational trauma that ensnares so many.

On a sunnier note, she has reconnected with her brother, Shawn. While he lives out west, he has taken the time to visit with Reynolds, even staying with her for a short time this past summer. She says he has been sober for two years and is doing well.

“I’m very proud of him.”

She also has five foster sisters with whom she is close.

Jordan, our server, clears our plates and tells us to take our time.

paint sessions to her followers. Photo: Roderick Benns.

Reynolds says she is realistic while also hopeful. “It sucks, you know, all the losses. But it’s also about appreciating what I do have here and the people in my life – which is really scary, because ultimately you could lose them. Loving people is hard.”

One day she plans on volunteering for Big Brothers Big Sisters, in recognition of what Sissy meant to her on her own journey. “I just need to stabilize a bit more,” she says, injecting learned caution into her life plans.

And she knows there are reasons to be thankful.

“Now I look at myself and I’m like, you know, you’ve come a long way.”

In the meantime, she will continue to lose herself in her painting. Or is it find herself? That’s what I decide to ask her as a parting question.

She takes a couple beats to answer.

“It feels like both. Sometimes I lose myself in my paintings when I just don’t want to come out of it. I’m stuck in my colours and the way they’re making me feel” with each brushstroke.

“It’s over a longer duration of time, I’m realizing, that you find out who you are.”

What a poignant story of struggle and redemption. How fortunate Reynolds is to have found a place in her art. She is very talented. I can understand why her work evokes in the author thoughts of tea and oranges.

I often think Post Traumatic Stress Disorder is an unfortunate misnomer, that it should be called Post Traumatic Stress Injury, because the symptoms are so often caused not by an individual’s internal mess but by external war or criminal injury. It goes to liability, too. Who pays? Too often, no one, as blame is shifted to the victim or society.

There should be a label for the symptoms of Current Traumatic Stress injuries too because so many in today’s world experience symptoms from ongoing trauma throughout their lives so that it becomes a theme that defines them.

I often wonder too how common are the human horrors covered up by good manners and afternoon tea. That other world that art so often opens us to is one of shared secrets.